I grew up in a home with four siblings, with birth years between 1959 and 1966. If you do the math, that adds up to a whole lot of young bodies in a 2000-sq.-ft. home. As a single parent, Mom did the best she could to nurture our varied interests.

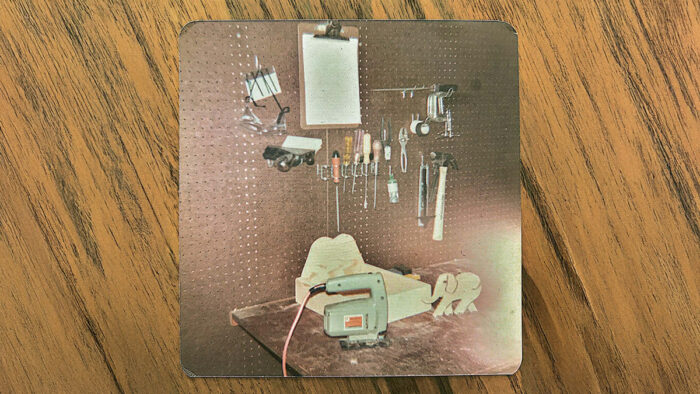

I was the only one with wood in my DNA. I had a basement workshop with a pegboard where I hung my tools, and it was a refuge. I asked for an electric jigsaw for Christmas one year and was thrilled to find it under the tree. A high school neighbor showed me how to use it, because there was no one in my extended family who knew anything about tools.

I remember riding my bicycle to the lumberyard and buying a piece of plywood—not a full 4×8 sheet but an offcut. Still, it was plenty big. I wrestled it onto my bike to walk it home, balancing it on the seat and handlebars. The trip, a couple of miles, was slow going, as you can imagine. I would get about 5 yards and the plywood would topple off. An older kid saw me and helped for a few blocks, steering the bike as I pushed from behind. I was someone with determination, and I needed this plywood for the roof of my latest tree house.

I could not wait for seventh grade to arrive so that I would finally be able to take woodshop. When it did arrive, in 1972, changes were afoot in both the school district and the nation at large. We learned on the first day that some boys would be assigned to metal shop or woodshop in the first semester, and the others would take home economics. I was crushed when my schedule said home economics when it should have said woodshop. This was not a mistake; it was the unluck of the draw, and tears flowed when I got home.

Of course, the girls got the same deal, and I knew deep down, despite my disappointment, that it was right—that shop class shouldn’t be gender specific, that all should have the chance to be introduced to the craft, especially at such an impressionable age.

My luck didn’t get any better the second semester, when I was assigned to metal shop. By this time, I was convinced that my passion would go no further than my basement workshop.

But finally, in eighth grade, the day came to step into the woodshop. Now I would be given the key to unlock the wonders of the wood world—or so I thought. What I received instead was another shock: A middle school woodshop is only as good as the instructor. “Jaded,” “uninspired,” and “close to retirement” best describe the teacher that year, and a knickknack shelf out of pine was the project we were all assigned. It was nailed together and heavily sanded.

The next year, woodshop was an elective, and I elected it. The projects were a little more interesting, but I found that I was happier in my basement workshop making exactly what I wanted. I skipped class more than I attended, and I once got detention for using an air hose to shoot a dowel across the room. Was this the beginning of an illustrious furniture-making career?

Despite the false starts, the wood world continued to call. After receiving a university degree in English, I learned to build houses. Then I discovered the world of fine furniture as an apprentice to a maker in Seattle. Finally, I reached the woodshop pinnacle by spending two years studying with Jim Krenov in California before launching my own career back on the East Coast.

When I teach now, I am not jaded. All I need to do is reach back 50 years to the feelings of enthusiasm and contentment that I had in my basement workshop, immersed in what felt so natural, and I pass that on.

While teaching recently at a craft school, I met a teacher who had experienced the home economics/woodshop switcheroo from the other side. But she had not been upset by it. Shop class tapped into her own budding desire to work with her hands and explore materials, something that may have previously been unavailable to her at school. Her medium turned out to be metal, and she creates the most extraordinary turned vessels and sculptures.

In time we get to where we want to be.

-Timothy Coleman’s woodshop is a freestanding affair beside his house in Shelburne, Mass. It’s still a refuge, though it has no pegboard.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.