Although he never wrote for Fine Woodworking and his work never appeared in the magazine, Michael Burns had a tremendous impact on woodworking as an instructor at the Krenov School in Fort Bragg, Calif. His students are responsible for more than 100 articles in Fine Woodworking, and dozens have had their work featured in the Gallery. This profile features 11 tributes to Michael written by former students and others impacted by his life and teaching.

Perhaps you have heard of Michael Burns, but it is more likely you haven’t. If not, you may be wondering why Fine Woodworking magazine, a publication that rarely features profiles or tributes, is including a tribute to a woodworker who has never written for the magazine and whose work has never been shown in its pages. Though very much out of the public eye, Michael had an impact that can’t be denied—not just on Fine Woodworking magazine, but on contemporary woodworking over the last four decades.

With a Master’s degree in Agronomy from the University of California, Davis, Michael moved to Mendocino County in 1969 with plans to pursue a fisherman’s life. The vocation didn’t mix with his persistent, serious seasickness, so he began working as a carpenter and realized he had an affinity for woodworking.

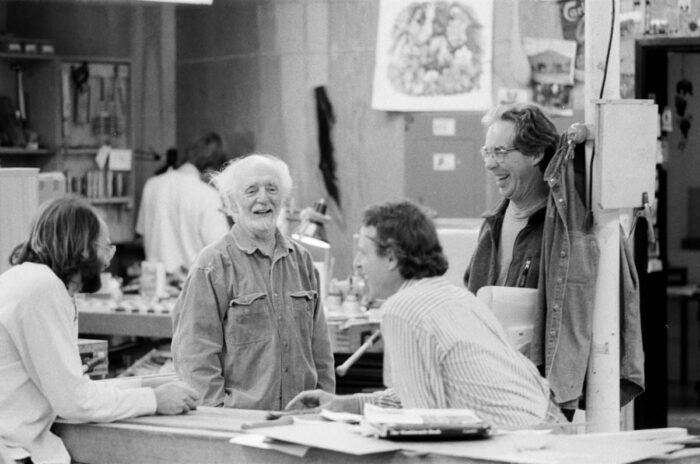

At that time, James Krenov was exploring the idea of teaching in the United States and was holding summer classes with the Mendocino Woodworkers Association. Inspired by Krenov’s teachings, Michael took some of those classes—and along with several other woodworkers, hoped to continue studying with Krenov. The group, including Krenov, came up with the idea for a permanent woodworking program. They approached the College of the Redwoods (CR) with the idea, planned the curriculum, and built the shop to house the program. Michael was instrumental in the creation of the CR Fine Woodworking Program; he began teaching part time in its first year (1981), moving quickly to a full-time position. When Krenov retired in 2002, Michael became the director of the program until his retirement in 2011, when Laura Mays became the director. (In 2016, the program transferred to Mendocino College and was officially renamed The Krenov School.)

Poring over the Fine Woodworking archives, I found that dozens of Michael’s students have written over 100 articles. There are dozens more whose work appears in the Gallery. While the Krenov School was built around James Krenov, it was Michael’s leadership and presence that nurtured something profound and extraordinary among the students and his fellow instructors—that made it less an institution and more a home. From that environment came immense talent, creativity, and community. The woodworkers Michael Burns nurtured went out into the woodworking wilds and became prolific makers, authors, and teachers.

I am grateful to have known Michael during the year I attended CR in ’06 and in the short visits I had with him when I’d return to Fort Bragg. But the real testament is in the words of the people whose lives intertwined with Michael’s. And the real lessons are in the way Michael worked and lived.

-Anissa Kapsales

Julie Burns

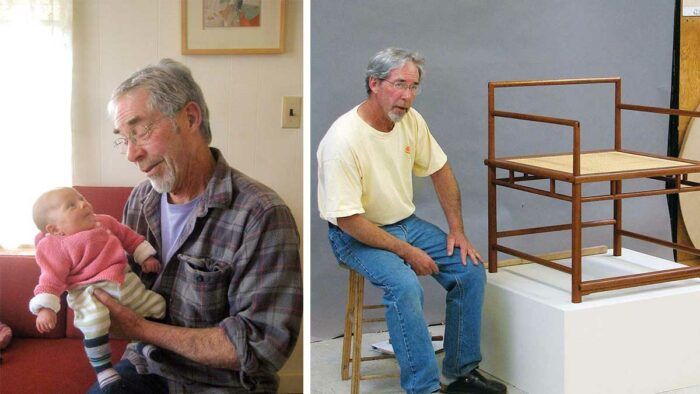

A life of work and play. Michael and Julie (an accomplished quilter) both moved to Mendocino on the same day in 1969, but didn’t meet each other until two years later at a mutual friend’s wedding. They started their life together in 1976 and lived happily together until he died.

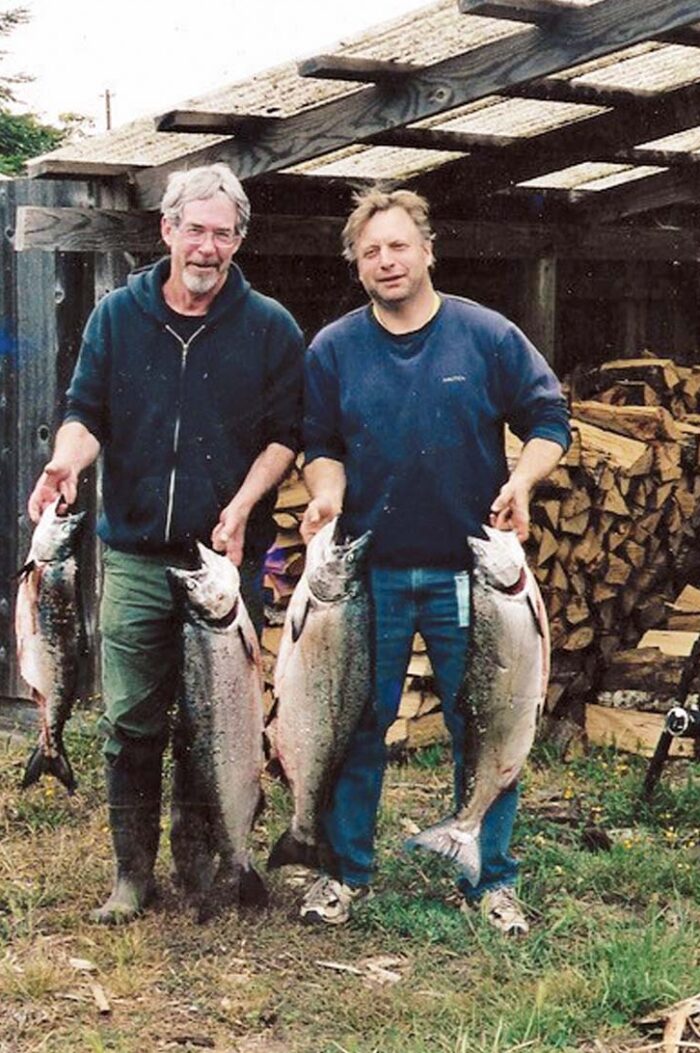

Michael built a life of pleasure. He loved to cook for his family and friends, plant potatoes in his garden, fish for salmon, and work in his shop. But it was the woodworking school where he focused his energy and attention. There he found great satisfaction in the relationships he fostered with his students. He took his responsibilities as a teacher seriously, but he equally valued the exchange that exists in the teaching dynamic. He encouraged his students to teach him about their interests, skills, and lives outside of class. He enjoyed meeting their families and friends. He welcomed them into his life. He would invite them to our home and to his shop and find ways to spend time with them. After his retirement, he continued to visit the school frequently, nurturing mutually beneficial relationships. He would never miss an opportunity to party with the students and staff. The traditional weekly after-school events, dubbed “Elephants,” were always sacred. I would not dream of planning a conflicting event on a Friday night.

As a result, we both made many lasting friends with students over the decades he taught, starting from the first year. These friendships have enriched our lives, sustaining and supporting us both. Since Michael’s death, this community of friends has rushed to comfort and assist me in every possible way. The Fine Woodworking school was and for me continues to be at the sparkling center of our social lives.

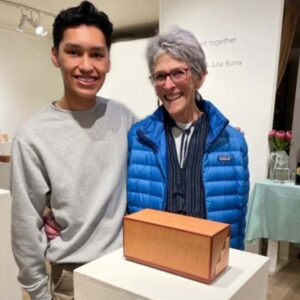

Michael never stopped being a teacher. Michael hired a young teenager, Eduardo, to help with chores around our home. From the beginning, Eduardo was drawn to Michael’s shop and all it contained: the books, the tools, the woodwork itself. Michael began sharing his knowledge, and Eduardo absorbed it all, reading the books, learning techniques, observing Michael’s work. Michael began to teach him the basics, and soon Eduardo was making his own tools and designing small pieces. Michael had great respect for Eduardo’s focus, eye, and skill. They worked together in the shop and Michael relished Eduardo’s companionship. The testament of Michael’s regard for Eduardo’s work is the final piece that Michael began. When he became too ill to complete “The Stairway to Heaven,” he asked Eduardo to finish it for him. Eduardo did so with grace and confidence. Now that Michael is gone, Eduardo, along with his family, have become an important part of my life, lending their support and help in so many ways. Eduardo is continuing his study of woodwork in his first classes this summer at the Krenov School.

Mark Taylor

Michael and I were close friends in the time after he retired from the Krenov School, but that friendship really had nothing to do with woodworking.

Michael and I were close friends in the time after he retired from the Krenov School, but that friendship really had nothing to do with woodworking.

Our bond, instead, was fishing, for which he had a great and lifelong passion. We shared a boat for the last 15 years or so and fished for salmon, rockfish, and crab out of Fort Bragg. Curiously—despite the length of time we spent together on trips out on the ocean—woodworking, teaching, and the craftsmanship he obviously possessed were rarely the subjects of conversation. Instead, we rode the roller-coaster of topics old men talk about—family, the fortunes of San Francisco sports teams, the absurdity of current events, ocean conditions, and how to keep the stupid boat afloat. Most of all, though, I remember how energized and happy he was when we were out there with our lines in the water. I think he was that way with all the facets of his life, whether they be family, woodworking, gardening, cooking, or chasing fish. He was a good woodworker, a good fisherman, and a good friend, and I’ll miss him dearly.

Rebecca Yaffe

Krenov School ’02, ’03

It’s difficult to pay tribute to Michael Burns in only a few paragraphs. If you mapped my adult life you would find him, and often his beloved Julie, at so many points along the way. More importantly, the way he showed up in each place is the way he resided everywhere—low-voiced, loving, curious, and intent on the moment, yet somehow casual or sideways about its potential import.

There are many memories on the map, starting with the first. On a trip up to the Mendocino coast to see the winter show, while I was secretly contemplating applying to the Fine Woodworking Program, Michael shook my hand, held on a moment longer than is normal, and looked me in the eyes. Surrounded by all the beautiful pieces and devotees, my heart solidified that it was meant to be.

On school mornings, on what I called “Michael days,” he would sit next to me at my bench and ask me what I dreamt about the night before and about the latest school gossip. As he left, he would throw some words toward my piece—and he was almost always right, and always pushing me through my worry and procrastination.

His lectures—about tuning a tool, placing a hinge so a cabinet door swings right, or cutting dovetails—became lessons not just for woodworking but for growing into adulthood. “Everything is a kit,” and “Dovetails are a joint, not a philosophy.” Fixing what is wrong, not expecting it to start right but caring that it gets there, moving step by step, noticing what is at hand, trusting myself and acting on it—these lessons filter through to this day in my current work as nurse, as a parent, and as a person.

Michael officiated at our wedding (as he did for so many) with Julie as our witness. There are endless memories: Raising a kid here and becoming part of the place; watching how Michael and Julie kept tending in such consistent ways to us, to their people, to each other. Weeping in Michael’s garden when we told him and Julie we decided to separate.

Sitting in the hospital garden, listening to Michael tell me about spots on a CT that needed follow-up. Listening to his hope that it would be OK. Following his lead. Seeing him in his living room, lying on the couch under one of Julie’s quilts, with Julie there too—telling me which treatment he couldn’t or wouldn’t do anymore. Same quiet voice, same sideways way that speaks the truth.

The last days of Michael’s life were spent sitting vigil in the house with Julie. Carrying his sleeping body with some woodworkers/friends so we could set up a hospital bed. Seeing him open his eyes for a moment and look at me, knowing he trusted me. Feeling I became a nurse just to make that moment possible and easy.

This seems about me, but I’m trying to convey Michael’s magical and quiet way of showing up and showing how, which affected so many lives, including his own. He seemed to know just how precious life is, and how pleasurable it can be. He somehow divvied up his attention between his workshop, the school, his friends, his family, his sweetheart, his fishing, his garden, his daily food-making, and even his nap, and yet took away from none of them. Each thing was whole unto itself and yet connected by his particular way of making it right-sized, just so, precious, and beautiful.

Laura Mays

Krenov School ’02, ’03

I came to the Krenov School, like many before me, lured by words. Krenov’s books were half sense and half sensibility, a beautiful conglomerate of the pragmatic and the romantic. When I finally arrived at the school, what I found was a community, not a person. If Krenov was the wood and the words, Michael Burns, David Welter, and Jim Budlong were the joinery, the glue, and the finish. Michael Burns (or Mr. Burns, or Father Burns, as he was alternatively and affectionately known) shepherded us along through the planning and fine details, buoying us through the delayed gratification of this kind of work, making a community from a disparate group of wood nerds. But it was really his life that I most admired: his relationship with his wife, Julie; with friends; with his work; with fishing. When I finished up my second year and needed to ship my pieces back to Ireland, he was kind enough to lend me the use of his shop for two weeks to make crates, while he went to Oregon with his family to decompress from the school year. In that spring of 2003, when the U.S. was invading Iraq for a second time, Michael made “Woodworkers for Peace” placards for us students to carry in the protests in San Francisco, reminding us that even in our focused and rural woodworking community, we are part of the wider world.

When he retired and I took over his role at the school in the summer of 2011, Michael mentored me through my first tumultuous year, and I continued to turn to him for advice through the following years. No one else understood the complexities and subtleties of the role quite like he did. On occasion I was invited over to their house for a meal, which I remember never being anything but absolutely delicious; there was something so right-sized, a little bit humble, a little bit celebratory, warm, funny, loving. And after the meal, we would go to see what he was working on in his shop—usually something exquisite, and his shop was like a nest around him, the walls quite literally thick with memorabilia from years and years of gifts from former students who were now friends. Michael continued as an unassuming, gentle but important presence in the school, befriending the new students, offering nuggets of wisdom. Once or twice in each school year he would invite the class over to a presentation of his new work, always a reminder of how small and simple can be so so sweet.

At Elephants on a Friday night, which he came to religiously, he would sit on a bench at the fire, and maybe snuggle a little closer to whomever he was talking to, and maybe offer them a little nip from his hip flask, and ask after their sweetie, and how their work was going.

Eduardo Soria

Krenov School Summer Program ’24

I was 15 when I met Michael. He hired me to stack wood and mow his lawn. Before I met Michael, I had no woodworking experience. I was working for him for a month before I found out he was a woodworker, and the details and the smallness of his work amazed me.

I was 15 when I met Michael. He hired me to stack wood and mow his lawn. Before I met Michael, I had no woodworking experience. I was working for him for a month before I found out he was a woodworker, and the details and the smallness of his work amazed me.

Michael was truly a kind and generous man, not just with material things but with his time as well. When I told him I wanted to make a mallet, he went back into his shop and pulled out two pieces of wood and said, “Here, you can make it out of this wood.”

Once, when we were talking about his family, he mentioned that his grandsons weren’t into woodworking enough for him to pass on the knowledge. He said, “But you’re like my grandson.” We both laughed, but thinking about it now, he really did treat me like one. Most of the tools I have were gifts from Michael. He would always say, “Be my guest,” and he really did mean it. I remember one time he was going to give me a ride home; before we got in his truck, he said, “Eduardo you’re going to make it as a woodworker, because you get things done.”

When Michael asked me if I could help him finish his box, his final project, I was happy to help, but I was scared to finish it on my own. He had made the main box and the base. He wanted me to make the little trays that go inside. I needed Michael’s help, but he was very weak and sick. I tried my best without his guidance. I only needed one more day of work to finish the box—I was planning to show him the next day. I really wish Michael could have seen the finished box, but I hope I did him proud. I am very grateful for all that Michael did for me and for the time I spent with him.

When Michael asked me if I could help him finish his box, his final project, I was happy to help, but I was scared to finish it on my own. He had made the main box and the base. He wanted me to make the little trays that go inside. I needed Michael’s help, but he was very weak and sick. I tried my best without his guidance. I only needed one more day of work to finish the box—I was planning to show him the next day. I really wish Michael could have seen the finished box, but I hope I did him proud. I am very grateful for all that Michael did for me and for the time I spent with him.

Jim Budlong

Krenov School ’84, ’85

“Father Burns”—the memories flood through my mind, but ultimately keep coming back to what a good soul he was. My first year I was intimidated by Krenov and relied on not only Michael’s teaching support, but the personal caring and friendship he provided. He was always there for everyone: students, friends, family, and all those he married, including myself and Sue.

Over the years we shared so much: his understanding—and at times empathetic—friendship; the wins and losses of the Giants and Niners; the joys (and on a rare occasion the tribulations) of all the students who passed through the program; Friday lunches as well as birthday lunches; the great staff Christmas parties at his and Julie’s home; gardening successes and failures; his fishing stories; and, of course, the pleasures and frustrations of our woodworking. He was sorely missed at school when he retired, and now he will be missed by one and all forever. I am so lucky to have known him.

Ejler Hjorth-Westh

Krenov School ’91, ’92

It has been my good fortune to have touched many of the facets that made up the person Michael Burns; first as his student, and later as his colleague.

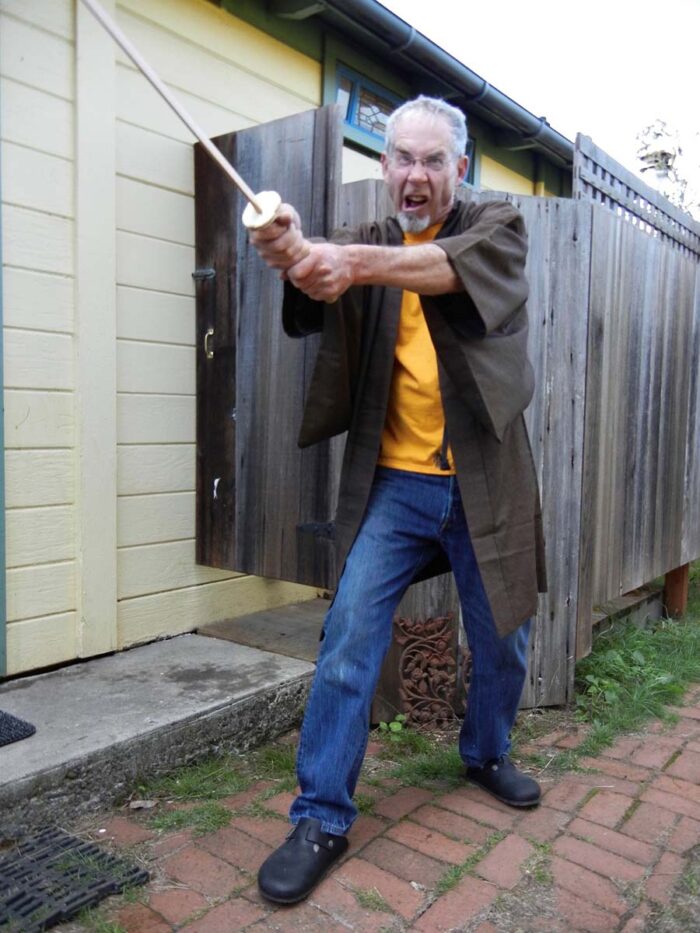

Teacher, mentor, counsellor, mediator, fisher, maker, friend—he was everything one could wish for, seeking a flourishing existence, and he shared generously with honest selflessness. Ever jovial and even-keeled, few things could knock him off balance.

There was one time, though. We shared a passion for ocean fishing, and catching king salmon was highest on the list. On one such fishing trip in his boat out of Noyo Harbor, Fort Bragg, Michael hooked a large salmon, which he patiently and calmly reeled toward the boat, where I was ready with the net. Not 30 ft. away a large sea lion reared its head, assessed the situation, and immediately dove for Michael’s salmon, which was chopped off and made away with, leaving only the head on the hook. He completely lost it! I witnessed in stunned silence as he expertly employed the worst words and phrases in the English language, while dancing a bizarre jig of contorted, pent-up rage: Yaaaaaaarrrh! After a brief, tense moment, he cracked up, and a release of laughter ensued.

Only by fishing did I ever get to see this side of Michael Burns, which brought to full spectrum the complexity of the man. Lucky me.

David Welter

Krenov School ’83, ’84

While few could say they were drawn to the Fine Woodworking Program due to the presence of Michael Burns on staff, many survived the intensity of the class because of him. Early on, he earned the nickname of “Father Burns” from many, including James Krenov, due to his even-handedness, his counseling, and his consoling nature.

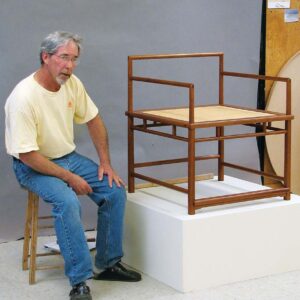

Michael was a fastidious craftworker who guided students of all levels, enabling them to strengthen their capabilities. His explorations in his private shop led to an expansion of the knowledge available to members of the course.

Despite a deteriorating relationship with Krenov, Michael managed to continue mentoring students constructively. After Krenov’s retirement, Michael safeguarded the integrity of the program for a further ten years. In his own retirement, Michael continued in his shop work and teaching until the very end.

Beyond the recognition of the emphasis on craft, the program is unique in bestowing a sense of community that spans the years. Michael’s empathy and his caring and nurturing nature are values that persist.

Greg Smith

Krenov School ’92, ‘93

I remember realizing, not long after starting my first year at the Fine Woodworking Program, that Michael was the community builder; the soul and glue that held the school together. He was not the reason I came to the school—I knew nothing about him—but he was instrumental in making it a place you really wanted to be. I was fortunate enough to share his shop with him for a couple of years after school. One day I was going on about how someday I was going to do this, or when things come together I would do such and such a thing; he stopped me and said, “But Greg, you’re living your life right now.”

Todd Sorenson

Krenov School ’01, ’02

Upon graduating from CR, I moved back to Seattle to work as an engineer and participate in a shared workspace. About a year out, Michael Burns went on sabbatical, and I replaced him for one semester. I never returned to Seattle. I started helping in the summer classes and was part-time faculty for Michael’s last five years when he went part-time. When David Welter decided to retire, I took over for him.

Michael helped me survive my time at CR, especially at the beginning when I was so uncertain. He seemed genuinely interested in me and everyone else—both in our woodworking and in our personal lives. He would be equally excited and worried for all of us depending on the situation. Michael was kind, generous, and funny. I used to think that we had a special friendship, but as time progressed it seemed like many people felt that way about him. He had a lot of room for all of us.

In the end, we just were friends, in work and play. I saw him almost every day, for brief moments or more. I worked with him, fished with him, and hung out with him and Julie. He was a part of our family. He married Heidi and me in our kitchen. He was there for the birth of our girls.

Michael used to have a circuit that he would do. It involved a trip to lumber store or the grocery store or both, and invariably it included a brief stopover at our house. As I felt forever busy and overwhelmed with our house and kids, I was usually home doing some chore. We would stop and hang out and discuss the events of the day and then he would move on. It is quieter now.

Michael was old enough to be my father, but I never really felt that way about him, even though he carried the “Father Burns” nickname forever. He was always so youthful in his attitude and the way he went about things. He was the epitome of cool: Always dressed better than most, with great hats; always changing his hairstyles, keeping it fun. Sweet man.

David Ryan

Krenov School ’89, ’91

I was a student of Michael’s for two years and his brother-in-law (I’m married to his sister) since 2001. Michael was an example of a person whose nature and abilities are ideally suited to their work. He was a true believer in the ways of James Krenov, with his impractical and uncompromising approach to the craft. As a teacher he was clear, thorough, and detailed. As director of the school, he had to balance out many diverse and occasionally fractious forces to keep things on track, and did so with good humor. His own woodworking embodied the same high standards and precision that he taught the students. From his home shop, a rebuilt one-car garage, emerged a steady series of remarkable pieces. He believed you should do the very best work you could and thereby find fulfillment. His often-repeated advice was, “Be happy in your work.” I think he was. By my rough count Michael must have taught 600 to 700 students in his tenure. Very few of these people remember him with anything less than affection.

Doug King

Krenov School ’06, ’07

The two years I spent at College of the Redwoods made up one of the most formative experiences of my life. Such an experience inherently comes with both successes and difficulties as there are high standards being pursued. Both in success and difficulty, Michael was there with me and for me. He was a steadying, calming, and encouraging presence for me during this time, and a bit of a father figure—I called him “Father Burns.” When I was overwhelmed because I was excited and wanted to do everything (but two years only allows for so much), he was there to talk me out of the tree. He was kind and fun, welcoming and encouraging, realistic and authentic. I reflect on my experiences at CR almost daily, as each member of the program played a unique and critical role in the collective success of the experience. Michael played a huge role in my time there. I will forever cherish all of those people.

Jay T. Scott

Krenov School ’01

Michael Burns was a master educator and woodworker. The College of the Redwoods Fine Woodworking Program, now the Krenov School, is a family of craftspeople because Michael raised us as his children. He loved the craft, but he loved the craftspeople more. Every year he worked tirelessly to join a group of strangers into a community that could support each other on the long arc that is the journey of the craftsperson. As “Father Burns,” he officiated the marriage of many of his students and their partners. He always encouraged us to be happy in our work. From his humble shop, smelling of woodsmoke, tobacco, and fresh shavings, came some of the sweetest pieces any of us had seen. As he aged, he showed us how perfect a simple box, made of some precious little plank, could be.

Michael Burns was a master educator and woodworker. The College of the Redwoods Fine Woodworking Program, now the Krenov School, is a family of craftspeople because Michael raised us as his children. He loved the craft, but he loved the craftspeople more. Every year he worked tirelessly to join a group of strangers into a community that could support each other on the long arc that is the journey of the craftsperson. As “Father Burns,” he officiated the marriage of many of his students and their partners. He always encouraged us to be happy in our work. From his humble shop, smelling of woodsmoke, tobacco, and fresh shavings, came some of the sweetest pieces any of us had seen. As he aged, he showed us how perfect a simple box, made of some precious little plank, could be.

Michael continued making and teaching into his last days. His final piece was finished under his direction by his last student. Often when people speak of Michael, they mirror his humble words.

No longer. Robert Michael Burns was the greatest man to have ever lived. He was like a Greek God. We were all lucky to know him. We have walked amongst giants.

Tim Coleman

Krenov School ’88

I was barely an adult when I started at CR, and Michael’s example of living simply in a place you love, and experiencing joyous engagement in one’s work, has been a model that I have strived for ever since. As a young student, I could easily be thrown off-kilter by things going wrong on a project. I remember Michael coming to my bench after I had botched an important process and was overly upset. He commiserated for a few minutes, offered ideas for some corrective measures, and then reminded me, “Tim, it’s just a piece of furniture.”

I called the school a couple of years after I graduated. I was on the East Coast, trying to make a go of it on my own as a craftsperson, working all the time, raising a couple of kids, and just making ends meet. Michael picked up the phone. I told him what I was working on and how I would bring my two-year-old daughter to the shop every afternoon. “It’s important, what you’re doing with your kids,” he said. “I applaud you.” Applause from Michael Burns at that moment meant the world to me and helped give me the courage and perspective to carry on.

Sign up for eletters today and get the latest techniques and how-to from Fine Woodworking, plus special offers.